April Whittington

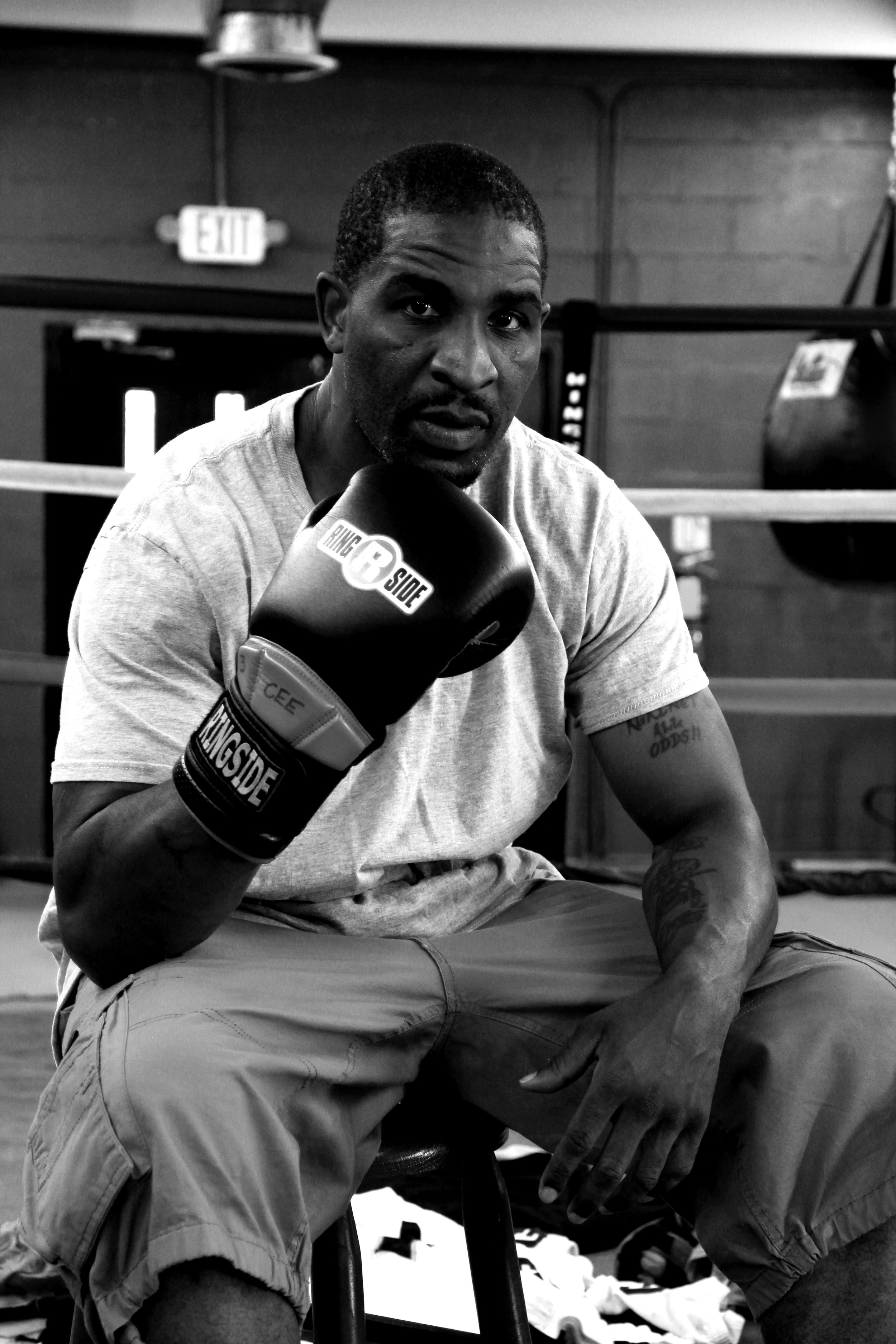

Local barber, writer, and activist. Student at Express Cuts Academy.

“I am all about women being liberated and being strong, and I do stand up for myself, but men…..how are they going to be leaders if they don’t even have a good haircut? And that is what I say to them.”

Full Interview

April, tell me about yourself.

I feel that God put me here to share. So currently I do that through being a motivational speaker and a writer. But my biggest passion right now is barbering, cutting hair. I am a learner. I take time to learn. I get to know people for who they really are. I don’t believe in staying stagnate in negative places; that is why I like cutting men’s hair because I enjoy making them look really good while also pouring into them in a positive way. I am a writer and a barber. They are so unrelated but also the same. You wouldn’t believe my story.

You can’t leave me hanging like that…

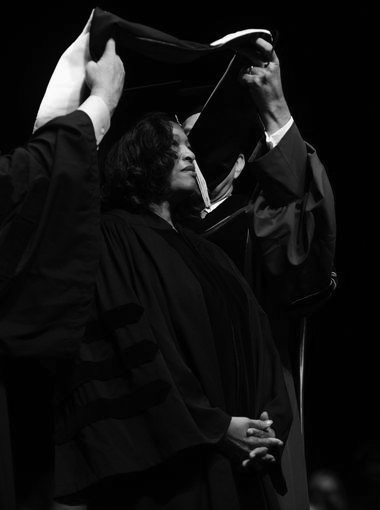

I am just an animated person. The reason I am animated is because I had a very rough childhood. It is not a pity story; sure, you could feel sorry for me, but that’s not my story. I am bigger than that. I have gone from sleeping in my car with my son when he was one, to now he is 19 and graduating with a diploma after spending his elementary and middle school education in special-ed. In ninth grade when he wanted to go into regular classes, I had him write a two page essay on why. I am not going to raise a man who feels that he needs to do things to make it look a certain way. It took him four days…the heart is all that matters. I am so vocal about the things I am passionate about because there is so much negative. We aren’t going to fix it all in one day, but at some point, someone has got to take a stand.

What led you into the line of work you are in today?

I have been cutting hair for years. I have always been into it and thought it was kind of interesting. I tried to go to barber school when I was nineteen, but I was not able to focus and finish. I just wasn’t ready. When I had my son at 22, I always cut his hair. I was the family and close friend barber. I knew how to do the basic even-cut, a bald-fade, and a blowout-fade. I couldn’t really promote myself to the public because I wasn’t licensed.

When did that change?

So last year, I realized that I needed to make a change from my corporate job. I was a stay-at-home writer for a few years and then took on another job that I ultimately was not happy in. After a negative experience with a manager, I left work that day and immediately went and registered for school that afternoon. That is how I ended up here.

What do you love about being a Barber?

Cutting hair for me is immediate gratification. A haircut can change your life. I am obsessed with men’s fashion: I love men’s clothes. When I look at men I think, the least you can do, for the community, is have a nice haircut. I am all about women being liberated and being strong, and I do stand up for myself, but men…..how are they going to be leaders if they don’t even have a good haircut? And that is what I say to them.

You seem to really care about your customers.

I really take pride in my haircuts, and I’m not going to send someone out of there looking bad. When I am cutting a man’s hair, I am with him for at least twenty to thirty minutes. This is a very intimate time. Obviously we aren’t talking about anything inappropriate, but I am going to have my hands directly on his head for this entire time. That is a transfer of energy. He is going to communicate with me, and it is very important to me that I have the space to receive and give back positively.

Tell me about working in West Greenville.

Everyone just knows that this is the barber school. It used to be on Pleasantburg, and I was there for three months before we moved to the Village. I feel like West Greenville benefits from us being there. I have had people stop me in public— people whose hair I have cut— and thank me for making them feel a certain way. I happen to know how to cut hair, which is good. But I also make people feel great just by being authentic. I am very real all the time and people feel a good feeling from that. Some people don’t like it because some people don’t like the truth. People who know me tend to say I am very difficult to deal with because I am just very firm about boundaries and I don’t believe in being fake.

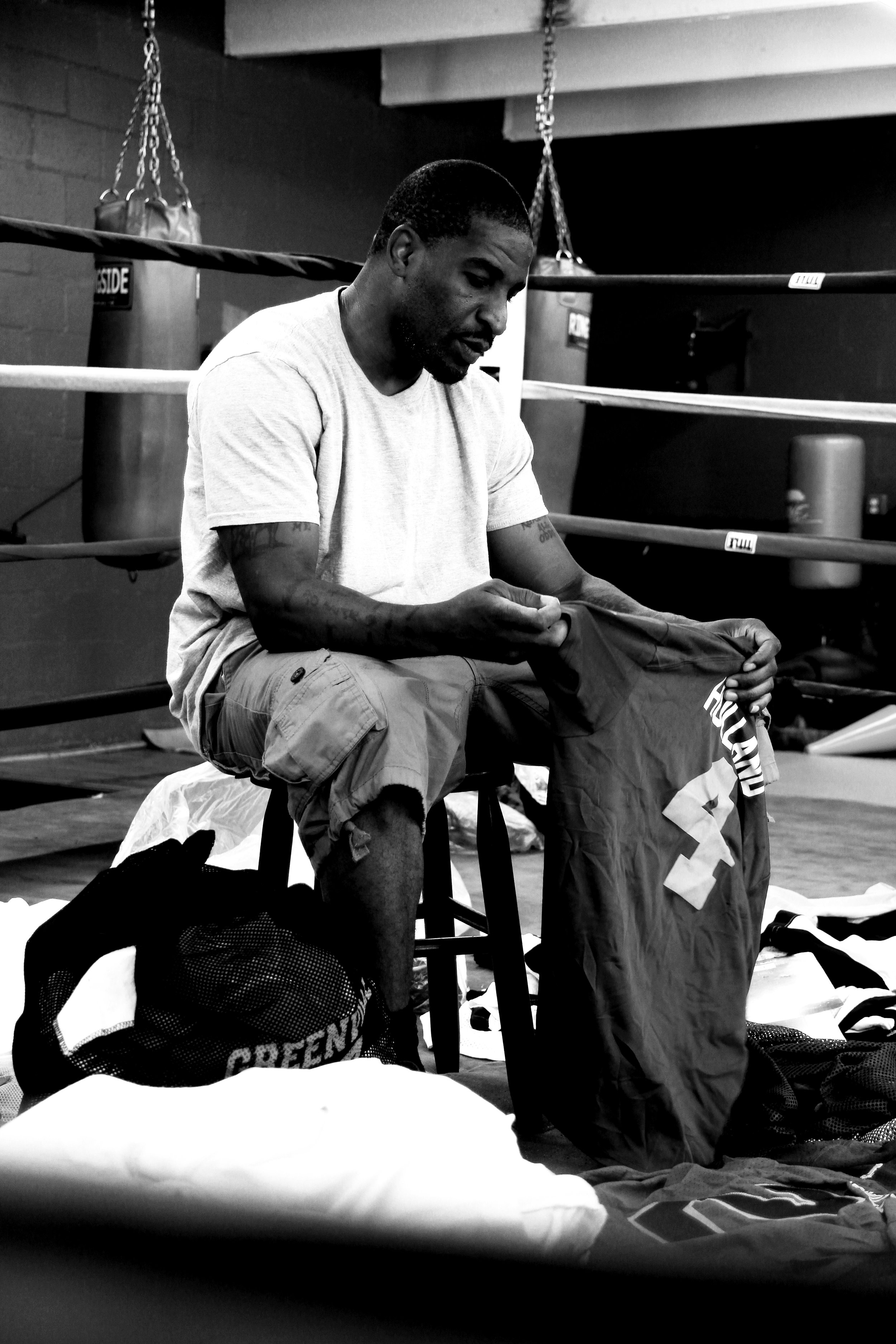

Tell me about your clientele.

You have people who come in and have no economic standing. You know their situation is rough. That haircut is probably the only eight dollars they have. And then you have those people who come in and only want to spend eight dollars because they only want to spend eight dollars. It is a very interesting industry. Yes, it does make more sense for people who are lower income to come to us if they can get a good cut. We are cheaper, just by the nature of being a school. There are a lot of people in the lower income areas who need help getting a haircut. I’ve cut somebody’s hair before and they cried when I finished and it was because he told me he hadn’t been able to afford one. And most people are about to spend eight dollars on lunch.

What cultivated this desire for service in you?

I like to give to people, because that was an experience I did not have growing up. When I was young, I was often getting into trouble. I would steal, I would lie, I was manipulative. I was in jail briefly before I had my son. But because of that, I was always getting put down. I was never uplifted, and my entire life, everyone focused on my negative. But when I decided to get my life together, that is exactly what it was. I go hard for whatever I do. Whichever side of the fence I am on, that is where I am at.

What helped you turn that corner, to turn your life around?

Having my son, Jamison Alexander Lewis, saved me. He is nineteen. God knows I give to those who need more than me. He knows how hard I give. So no matter how irresponsible I was or how much I was in and out of jail, he knew if he gave me another human….it changed my life.

You are a writer and a barber. Tell me about the work you do outside of the barbershop.

I have matured to the point where I can only do things for a purpose. Period. I worked for Sheen magazine as the Associate Managing Editor for several months but ultimately it came down to purpose. I wrote my first book in 2011 and I self-published in 2012. It is titled, It is My Fault. This book came from my Facebook statuses. When I first got the idea of publishing them in the format of a book, I went back and read all my statuses from the past year, and realized that it would be great content for a book. The theme is accepting responsibility for your wrong.

In addition, you are incredible active in the community…

I am part of the after-school cohesion program. I coach students in creative writing. I also do free writing camps for kids called Writing Connections. Writing is just relocating your thoughts, up here, to the paper. I believe that life goes on. I have had friends in high school who used to bully me, reach out because of my writing. It’s so incredible—that can be a reality.

I do Meals on Wheels, because I need to. With my ability and what I know, I need to. I have gone hungry before. You give these people a tray of food- you know what Lean Cuisine is?- That is the portion size of the food they get. You hand these people that tray, and they are about to cry, thanking you. It is unbelievable. It is very humbling. I do a lot.

What is one of your goals or aspirations looking ahead?

I want to have a barber truck one day. I don’t know when they are going to make it officially legal, but I want to have a mobile barber shop. I don’t think I can ever do enough to give. Barbering, for me, is a community service. You have got to give it away.